Silk Road Expedition

China, 2012

My love affair with the Silk Road began long before I ever stepped foot upon it; the romanticism of West China took hold when I looked at a missionary text as a boy that described the joys of martyrdom as the Maryknolls had their heads cut off by godless Turkistan warlords.

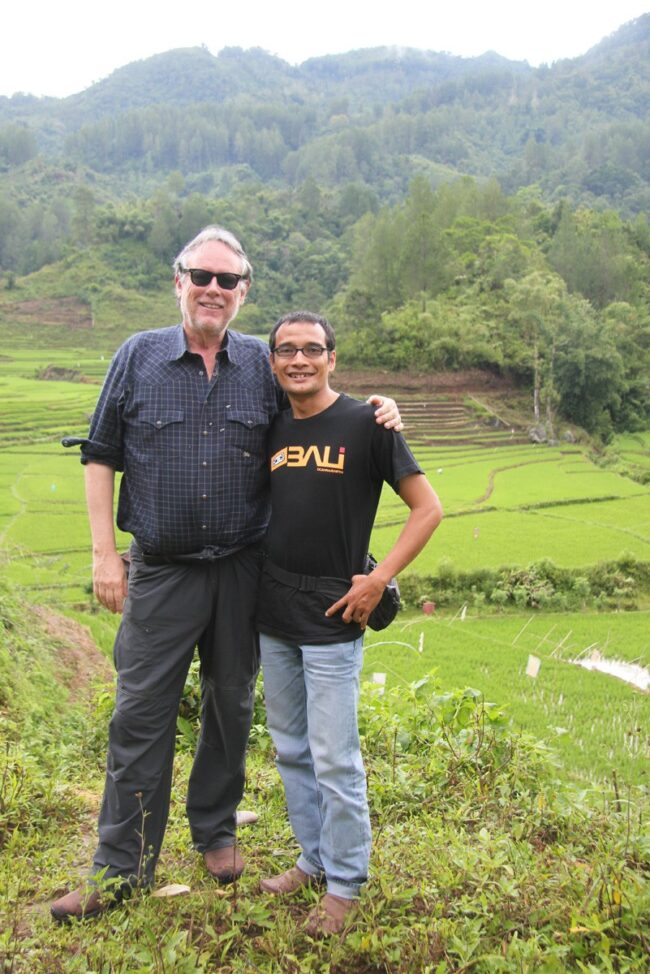

I was not convinced. But the call of the thousand-year-old Buddhist caves secreted on oases in one of the world’s driest deserts attracted me back to China in 2000 after not having been there since the “Fall of the Gang of Four” in 1978. There I met Miss Wenhua Liu who was to become one of the greatest friends of my life and someone I shared many a great adventure with (see China 2010 in this travel photo series of another trip together).

This time we decided to go back to see some of the highlights of from 12 years before and move East to some places we had never visited together.

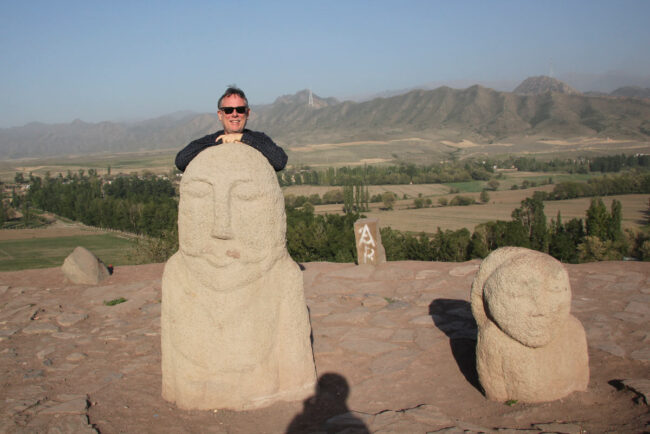

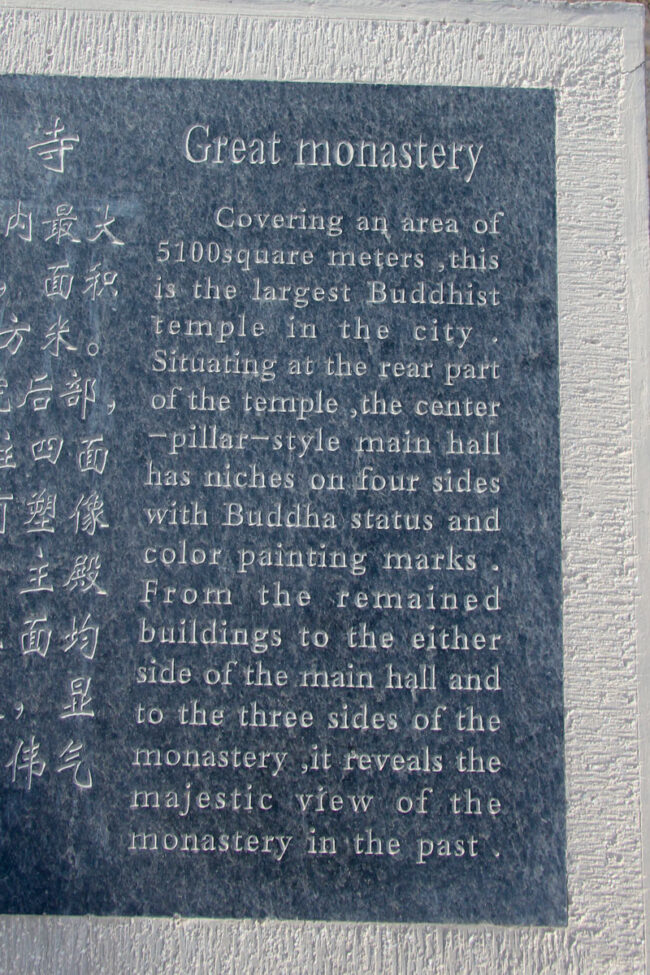

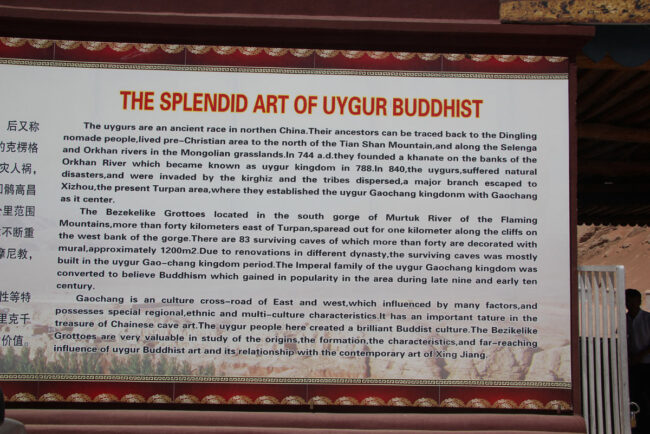

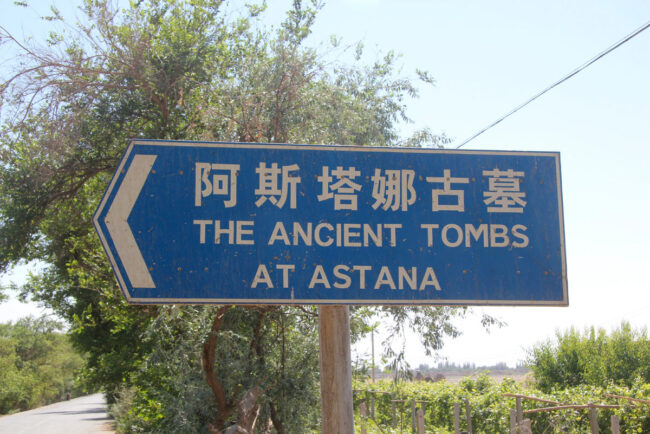

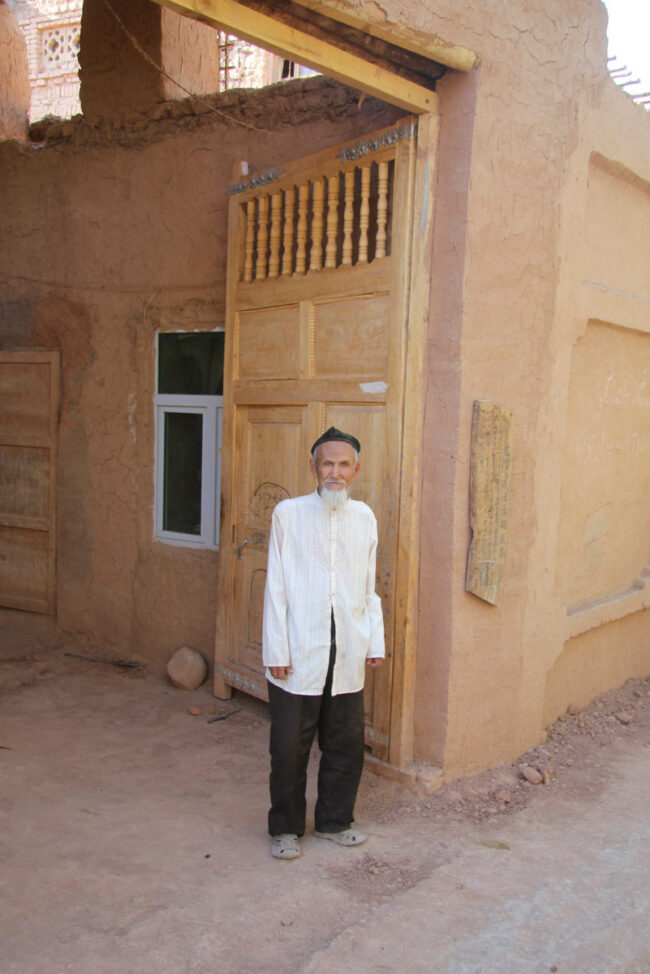

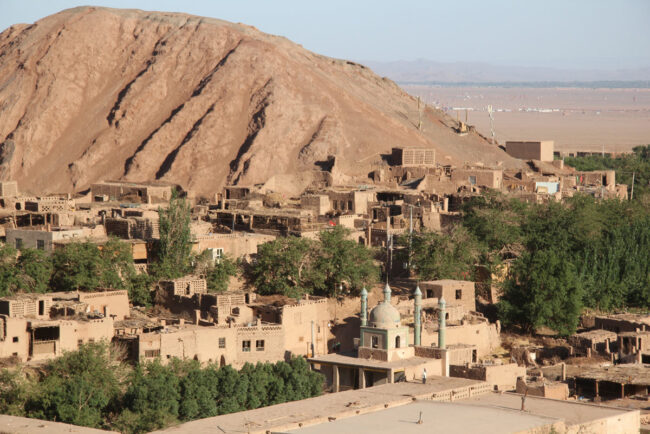

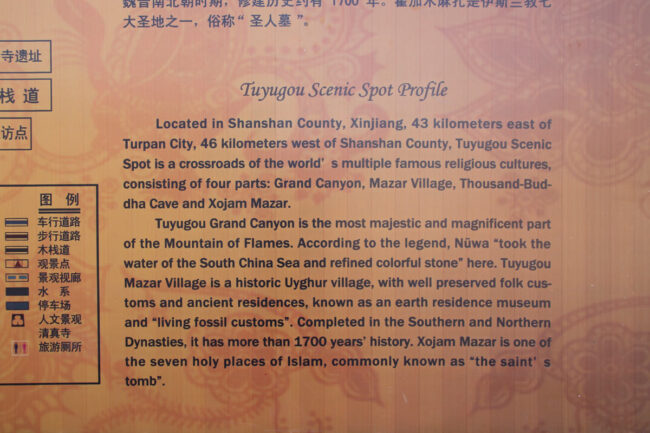

We started off with exploring her home city of Urmqi, the capital of the province of Xinjiang. It gets austere very quickly once one leaves town as we made our way to the Tang dynasty ruins in the area of Turfan (Turpan) including the ancient Uygur capital of Gaochang (856-1389 AD) and a marvelous mud architecture mosque from the Ming period. From there we made our way by night train to Dunhuang to visit the Mogao Caves with some 1000 years of Buddhist frescos beginning in 366 of the present era

I found the progression of painting styles most enlightening and was happy for the return visit. Especially not to be missed is the nearby museum that houses unexpectedly one of the greatest collections of large and important early Buddhist bronzes that came out of Tibet and were miraculously saved from being melted down to make farm tools.

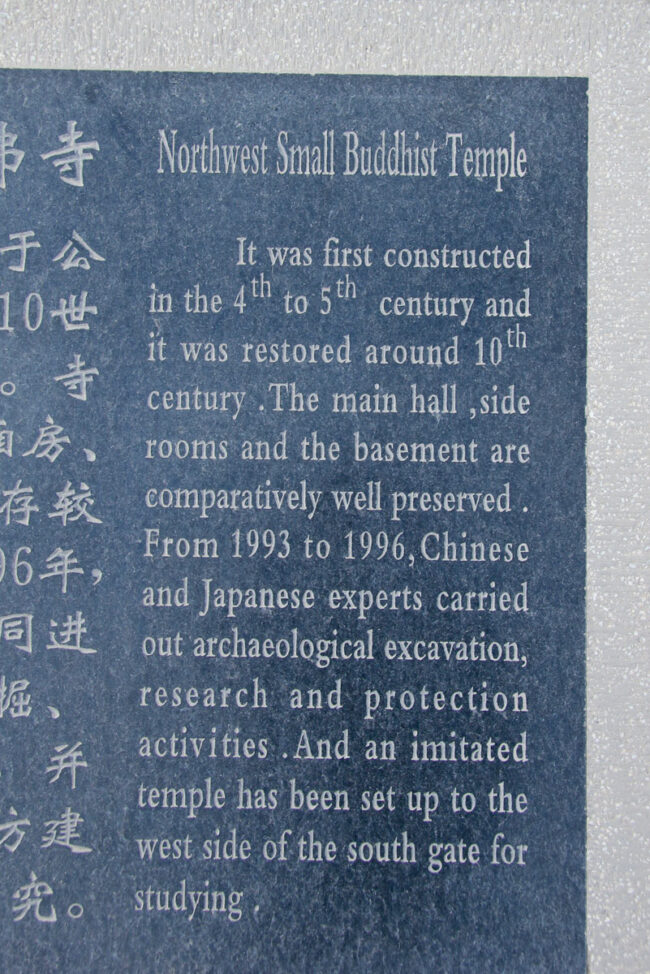

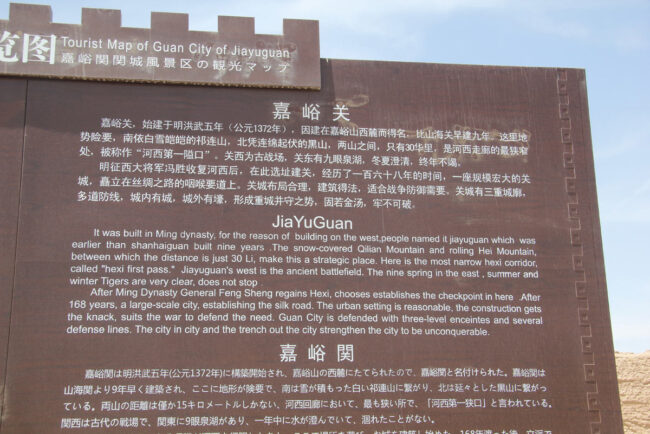

We took off from there overland to visit the Yulin Grottoes named for the elm trees that line the river cliffs where the caves are found. Dating from the Tang to the Ming, there are some unique paintings, different from the Mogao Caves and worth visiting, being some 100 kms from Dunhuang. The Jiayuguan Pass further down the long desert road has the most intact part of the Great Wall and an amazingly well preserved fort at the narrowest point of the western section of the Hexi Corridor of the Northern Silk Road. The Wei-Jin tombs were well worth a look in the same general area.

For me however the greatest discovery were the Binglinsi Grottoes some hours by car and boat to get to, but how fantastic! How exhilarating! And how maddening that, like everywhere else on this trip, I was not allowed to take photos of the truly important Wei and Sui Buddhist sculptures of the 6th-7th Centuries to share with you readers; but I can say that they were well worth the money paid for a special ticket to get into the special thousand Buddha caves…including climbing to the top of the Bamiyan-type giant sculpture of Maitreya, (the Buddha to come), carved into the cliff side 100 feet (27 meters) tall! Not for those with a fear of heights! Being the capital of Gansu, home of some of China’s most ancient cultures, Lanzhou has a fabulous museum that is highly recommended, with great dioramas of early man and the best Neolithic pottery exhibitions I have ever seen.