Cambodian Textiles

Coming March, 2024

Asia Week New York 2024

MARCH 14-20, 2024

Thursday, March 14th (evening) until

Wednesday, March 20th (morning)

PRIVATE VIEWING BY APPOINTMENT ONLY

To schedule a time please call (415) 378-0716

25 E 77th St, New York, NY

Digital Catalogs – Special Collections

Santa Fe / Objects of Art

August 10-13, 2023

El Museo Cultural – in the Railyard

555 Camino de la Familia, Santa Fe, NM 87501

In the recent publication, Textiles of Indonesia, Valerie Hector informs us that shells have been used in Southeast Asia as both ornament and currency for Millenia. Oliva shell beads were found in an archaeology site of Timor dating to circa 35,000 years ago and Nassarius shell beads were found in the same area dating to 4500 BCE.

Despite the emergence of the glass trade bead industry some two thousand years ago, hand fashioned shell disks continued to serve as a primary way of storing value and signaling prestige up through the 20th century for many ethnic groups of Southeast Asia and Oceania. This was owing to the extraordinary labor intensiveness in shell bead creation, and the principle that the further from the sea, the greater the value for all artifacts made from shell.

This small exhibition features shell artwork from some of the most legendary headhunting peoples of Asia,

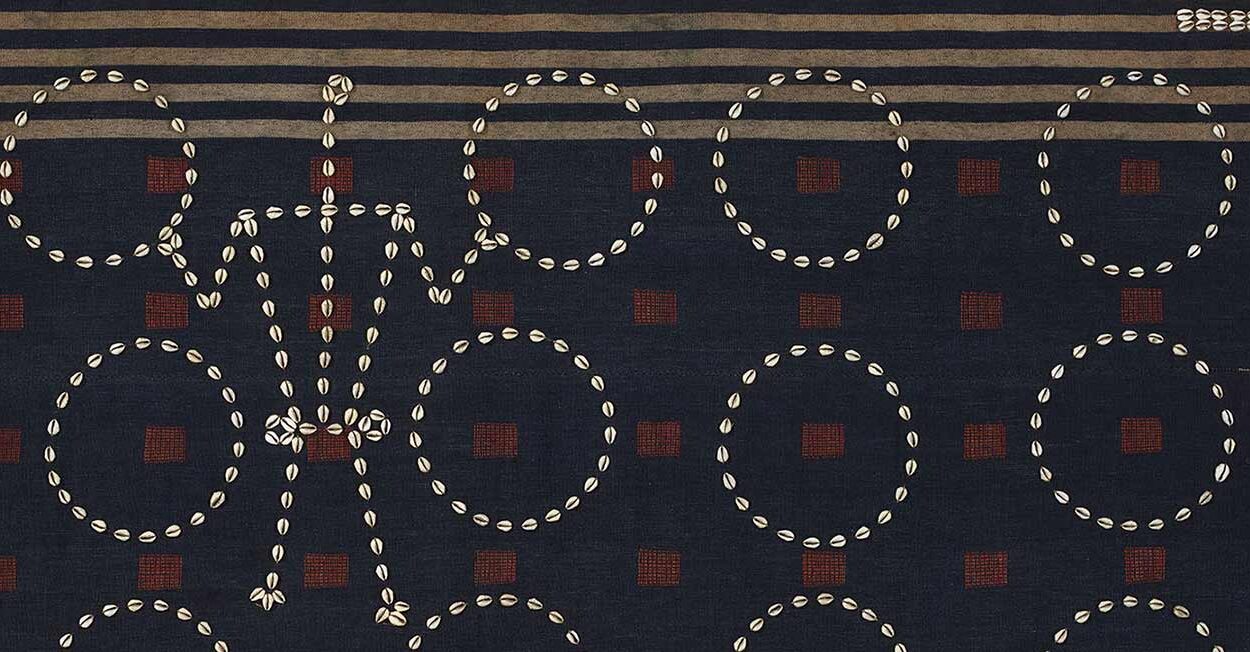

including the greatest shell-decorated garment in the world from the Atayal of Taiwan; a blouse decorated with mother of pearl shell beads from the B’laan of Mindanao, Philippines; an early warrior’s cape from the Naga with appliqued cowrie shells, making a human figure amid circles; and an extraordinary Naga necklace fashioned from giant clam, both from the northeastern highlands of India.

It is a pleasure to share this deeply meaningful group with you!

Asia Week New York

March 16-22, 2023

In-person by appointment in NYC

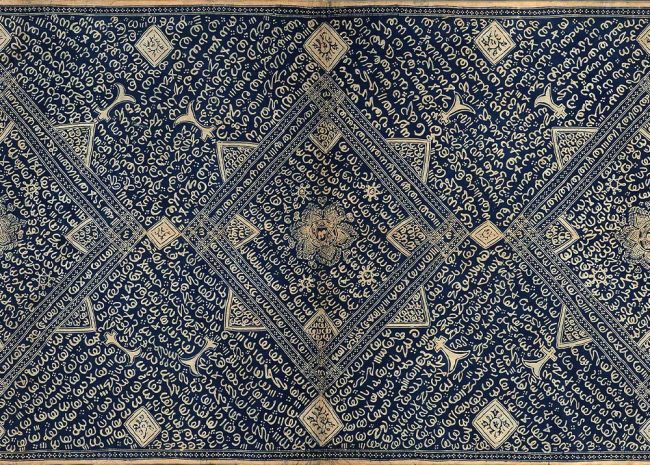

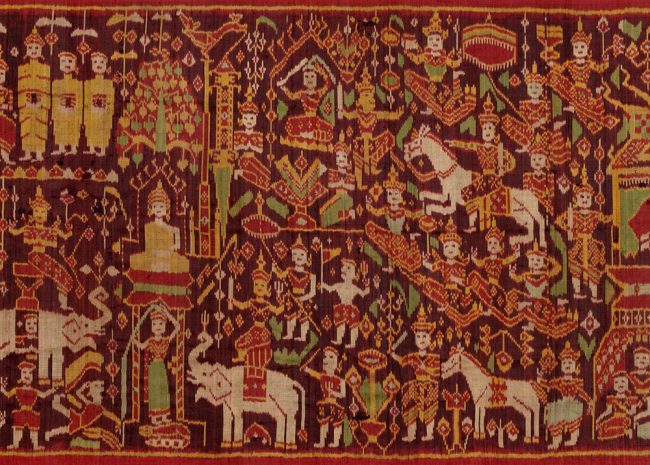

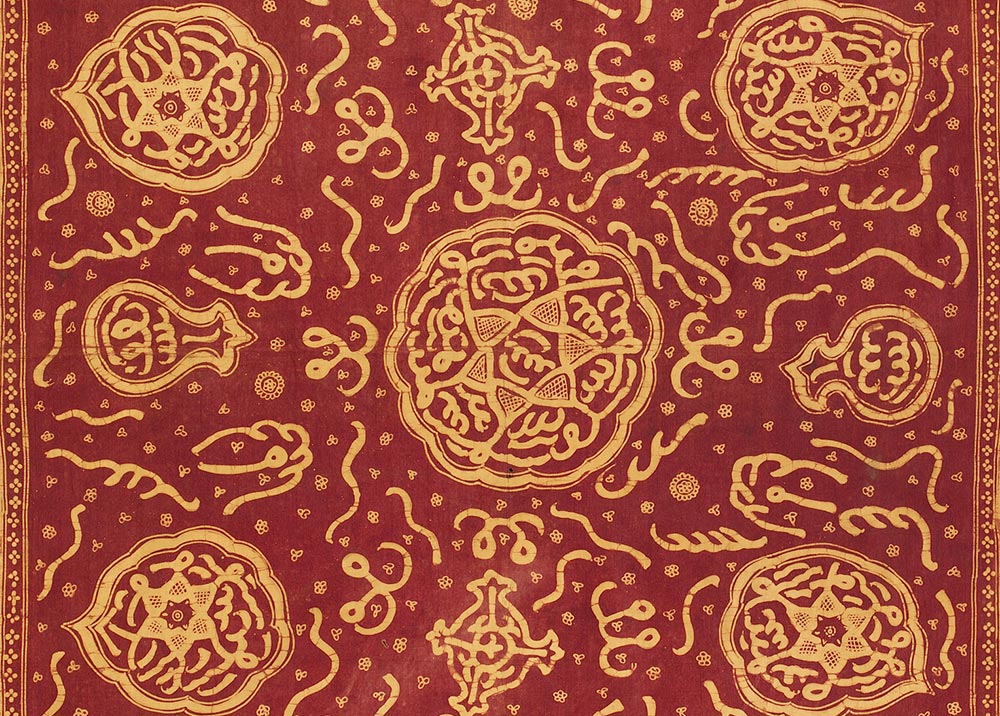

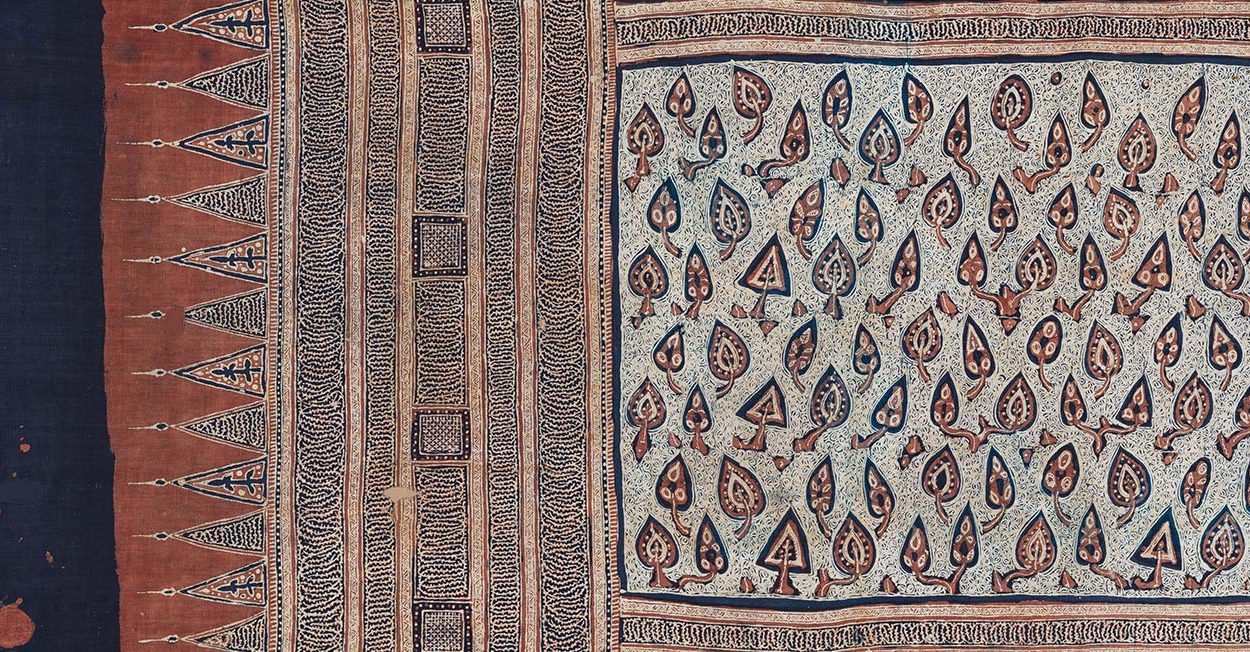

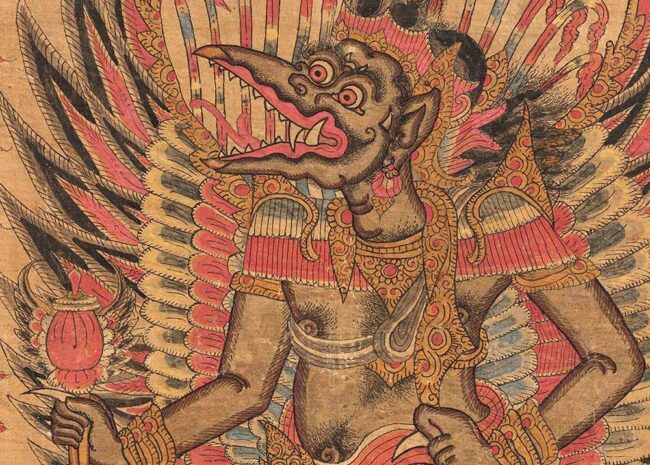

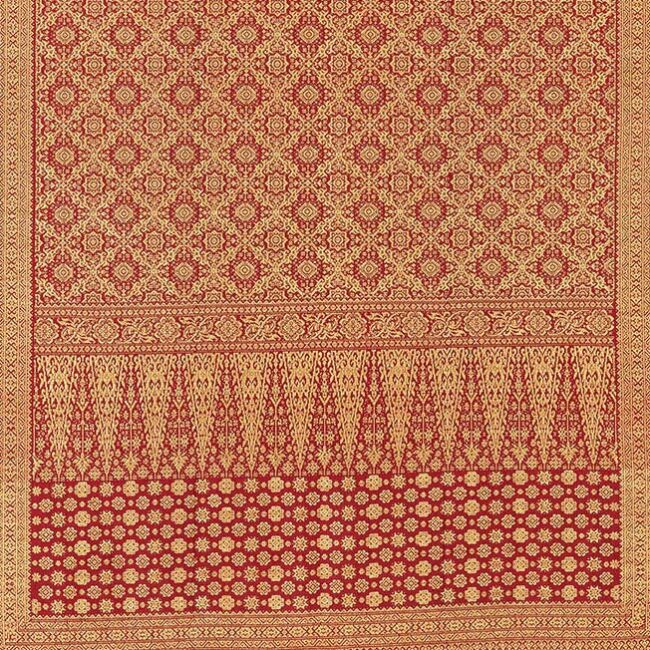

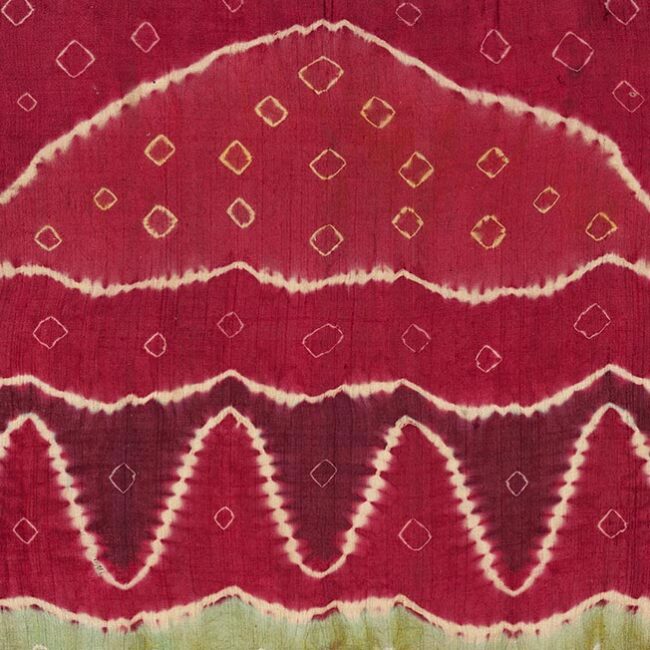

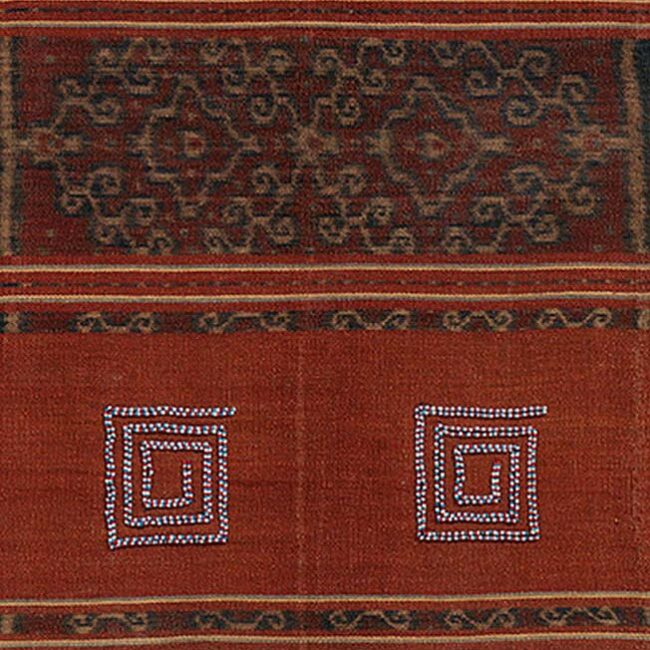

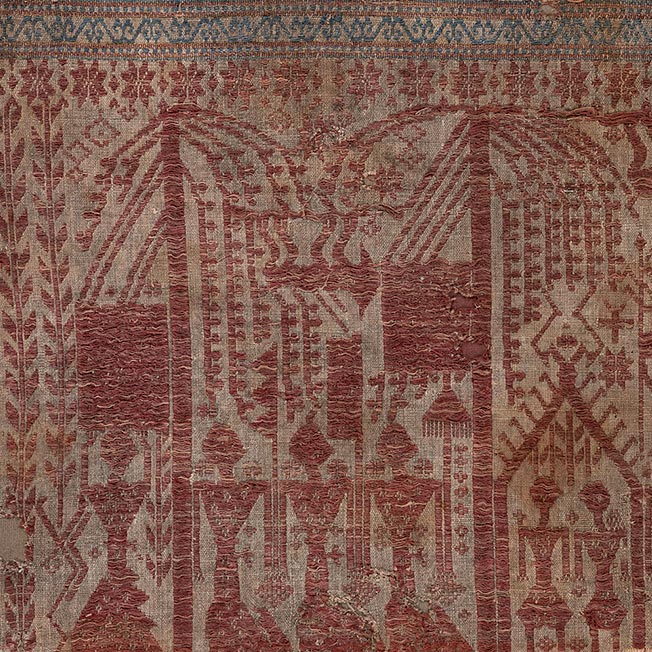

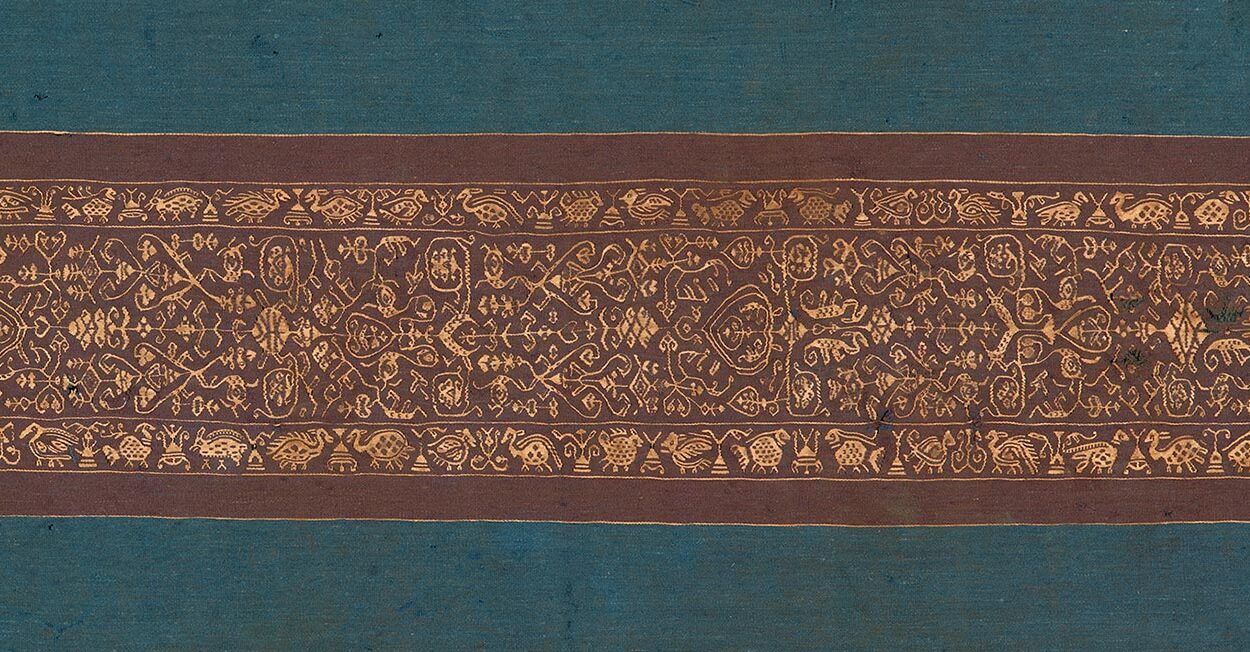

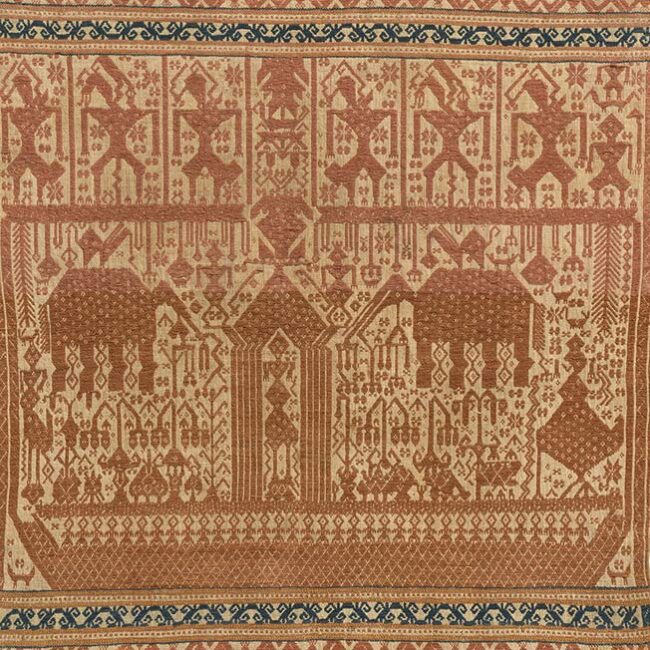

Thomas Murray is featuring a multiprong online and in person exhibition for Asia Week NYC 2003 that includes five exceptionally important textiles: Three Indian Trade Cloths of great rarity for the Indonesian Market and two iconic weavings from Lampung, Sumatra – a Double Red Ship Palepai and an early Pasisir Wedding Tampan.

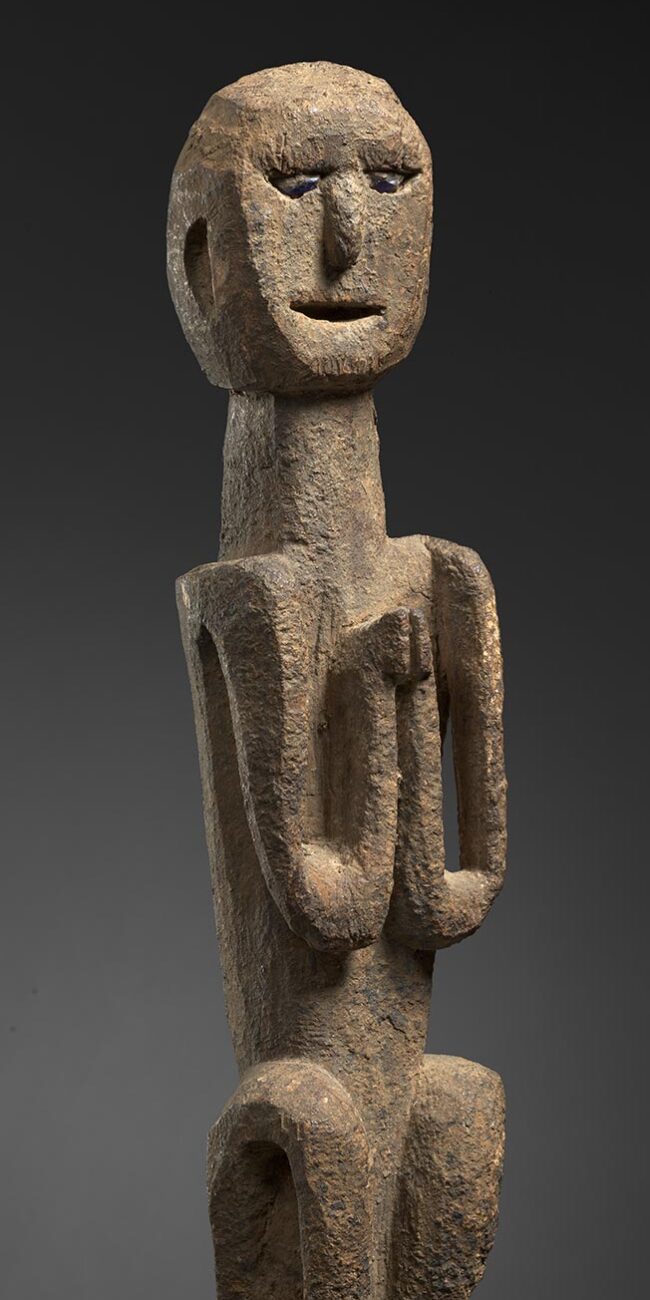

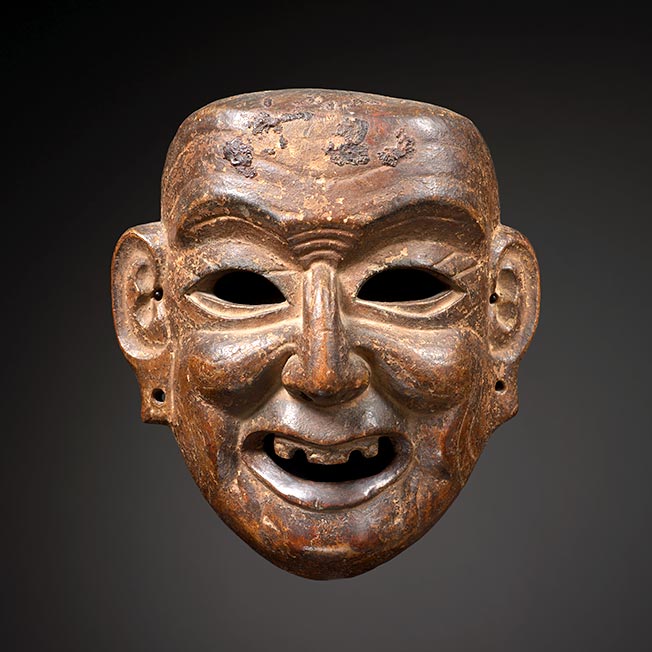

Introducing as well in wood are a fine Islamic calligraphic window with a ‘Seal of the Prophet’ inscription; two shamanic works from the indigenous Tao (Yami) People of Orchid Island, off the coast of Taiwan featuring compelling line drawing depictions of their primordial ancestor, Magamaog.

We are pleased to present antipodal jewelry offerings from Indonesia: a pair of gold earspools with diamond chips worn by royal Minangkabau women of West Sumatra and two precious and seldom seen gold ornaments from the remote easterly spice islands of Leti and Tanimbar.

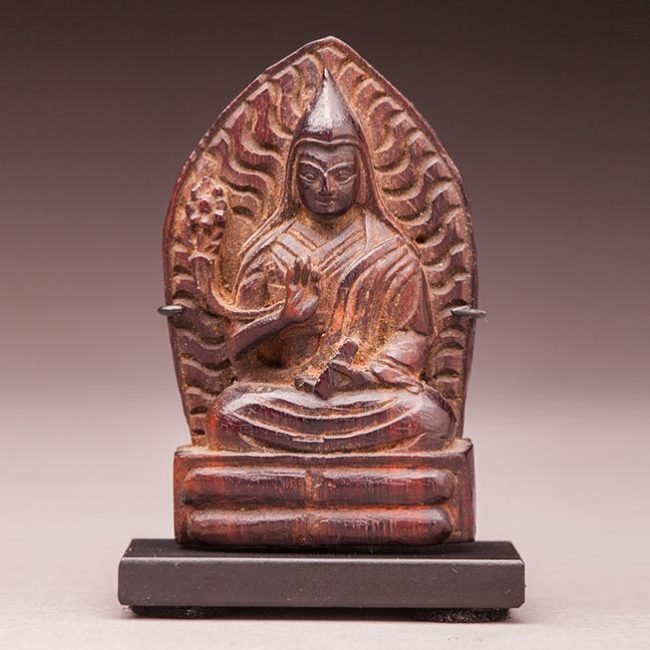

A private collection of bronze ‘found object’ charms, Thogchas, rounds out our exhibition. They were picked up from the soil of the Tibetan plateau by nomadic herders, who considered them magical ‘fall from sky’ talismans, with many dating 1000 years old or more. Formed over a 40 year period by an artist, this group is being offered as a whole

In the recent publication, Textiles of Indonesia, Valerie Hector informs us that shells have been used in Southeast Asia as both ornament and currency for Millenia. Oliva shell beads were found in an archaeology site of Timor dating to circa 35,000 years ago and Nassarius shell beads were found in the same area dating to 4500 BCE.

Despite the emergence of the glass trade bead industry some two thousand years ago, hand fashioned shell disks continued to serve as a primary way of storing value and signaling prestige up through the 20th century for many ethnic groups of Southeast Asia and Oceania. This was owing to the extraordinary labor intensiveness in shell bead creation, and the principle that the further from the sea, the greater the value for all artifacts made from shell.

This small exhibition features shell artwork from some of the most legendary headhunting peoples of Asia,

including the greatest shell-decorated garment in the world from the Atayal of Taiwan; a blouse decorated with mother of pearl shell beads from the B’laan of Mindanao, Philippines; an early warrior’s cape from the Naga with appliqued cowrie shells, making a human figure amid circles; and an extraordinary Naga necklace fashioned from giant clam, both from the northeastern highlands of India.

It is a pleasure to share this deeply meaningful group with you!

Small Buddhist Works of Art

In the recent publication, Textiles of Indonesia, Valerie Hector informs us that shells have been used in Southeast Asia as both ornament and currency for Millenia. Oliva shell beads were found in an archaeology site of Timor dating to circa 35,000 years ago and Nassarius shell beads were found in the same area dating to 4500 BCE.

Despite the emergence of the glass trade bead industry some two thousand years ago, hand fashioned shell disks continued to serve as a primary way of storing value and signaling prestige up through the 20th century for many ethnic groups of Southeast Asia and Oceania. This was owing to the extraordinary labor intensiveness in shell bead creation, and the principle that the further from the sea, the greater the value for all artifacts made from shell.

This small exhibition features shell artwork from some of the most legendary headhunting peoples of Asia,

including the greatest shell-decorated garment in the world from the Atayal of Taiwan; a blouse decorated with mother of pearl shell beads from the B’laan of Mindanao, Philippines; an early warrior’s cape from the Naga with appliqued cowrie shells, making a human figure amid circles; and an extraordinary Naga necklace fashioned from giant clam, both from the northeastern highlands of India.

It is a pleasure to share this deeply meaningful group with you!

On display In-person by appointment in NYC

March 16-22, 2023

The Art of Shell Beads

Asia Week NY / September 14-23, 2022

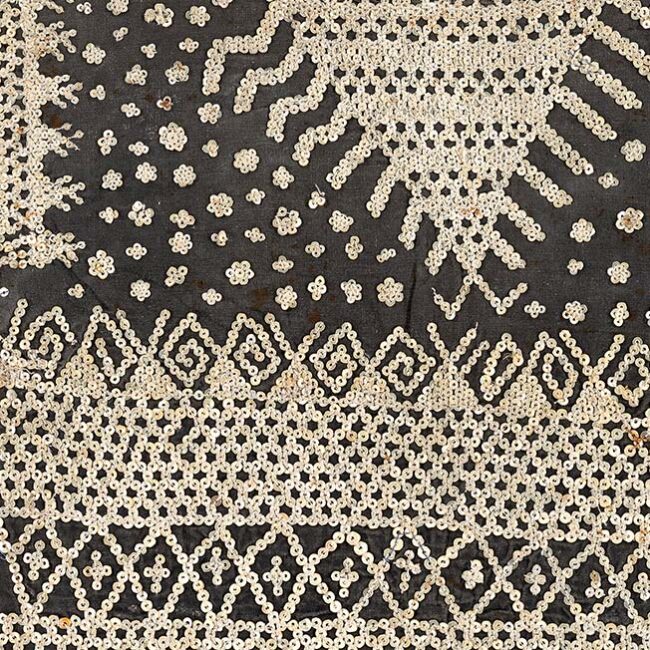

In the recent publication, Textiles of Indonesia, Valerie Hector informs us that shells have been used in Southeast Asia as both ornament and currency for Millenia. Oliva shell beads were found in an archaeology site of Timor dating to circa 35,000 years ago and Nassarius shell beads were found in the same area dating to 4500 BCE.

Despite the emergence of the glass trade bead industry some two thousand years ago, hand fashioned shell disks continued to serve as a primary way of storing value and signaling prestige up through the 20th century for many ethnic groups of Southeast Asia and Oceania. This was owing to the extraordinary labor intensiveness in shell bead creation, and the principle that the further from the sea, the greater the value for all artifacts made from shell.

This small exhibition features shell artwork from some of the most legendary headhunting peoples of Asia,

including the greatest shell-decorated garment in the world from the Atayal of Taiwan; a blouse decorated with mother of pearl shell beads from the B’laan of Mindanao, Philippines; an early warrior’s cape from the Naga with appliqued cowrie shells, making a human figure amid circles; and an extraordinary Naga necklace fashioned from giant clam, both from the northeastern highlands of India.

It is a pleasure to share this deeply meaningful group with you!

For further reading:

Bednarik, Robert G. “Beads and the Origins of Symbolism”

Draguet, Michel (2018) NAGA, Awe Inspiring Beauty, fig 236, p 306

Francis, P. (1989d). The Manufacture of Beads from Shell. In C. F. Hayes III (Ed.), Proceedings of the 1986 Shell Bead Conference: Selected Papers (pp. 25-36). Rochester Museum and Science Center.

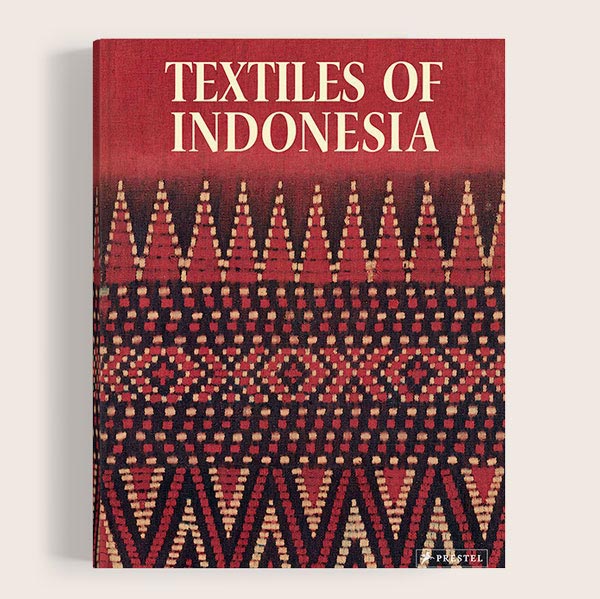

Hector, Valerie. (2022) “Indonesian Beadwork” in Textiles of Indonesia, Prestel

Langley, Michelle and O’Connor, Sue (2015) “6500-Year-old Nassarius shell appliques in Timor-Leste: Technological and use wear analyses” Journal of Archeological Science

HALI Fair 2022

May 20-30, 2022

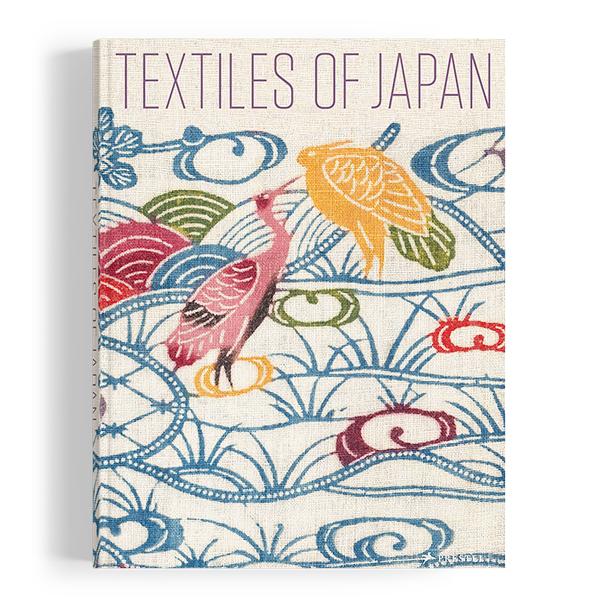

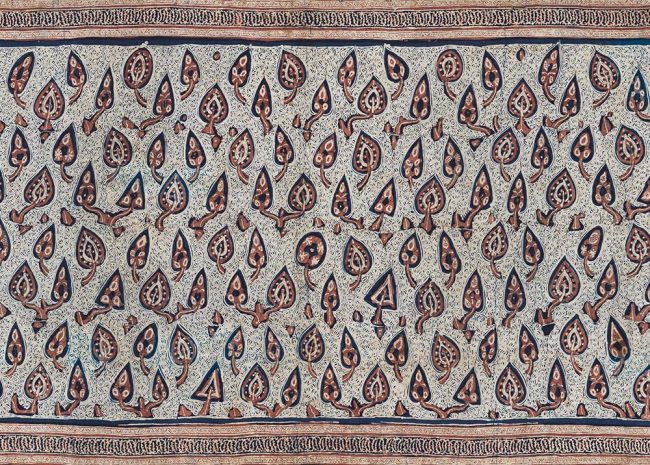

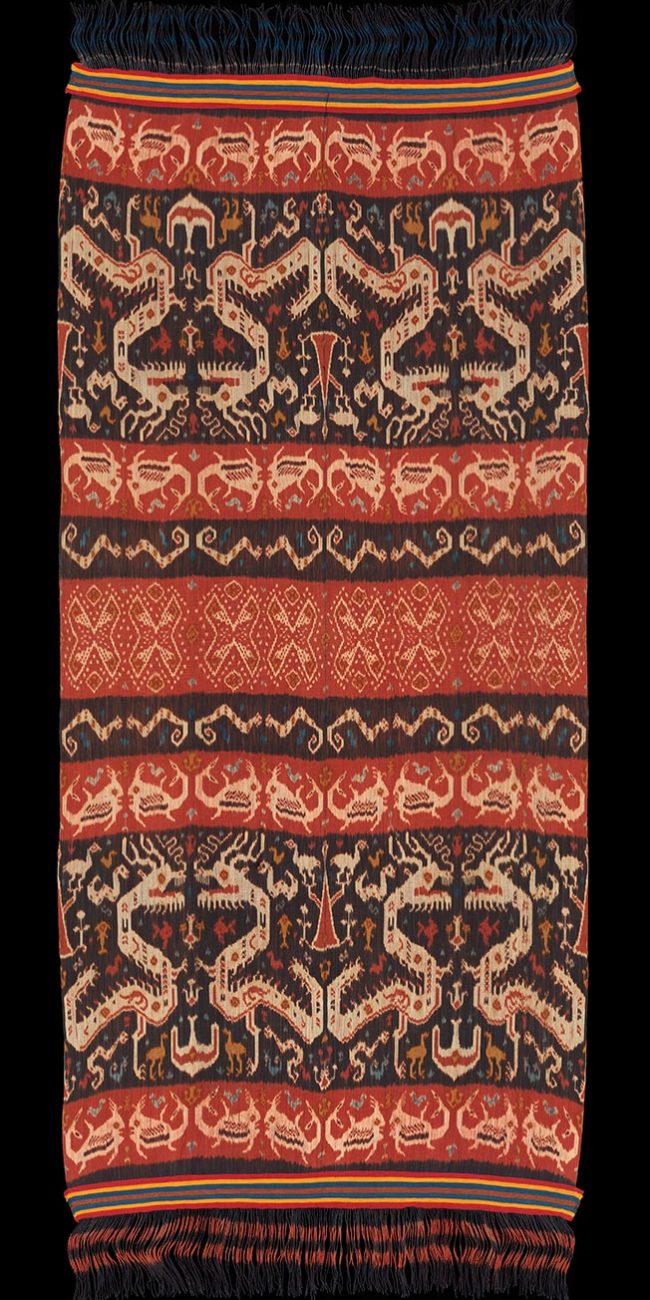

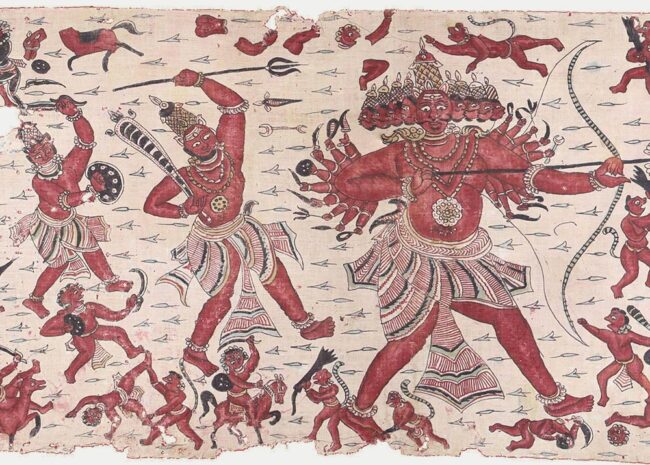

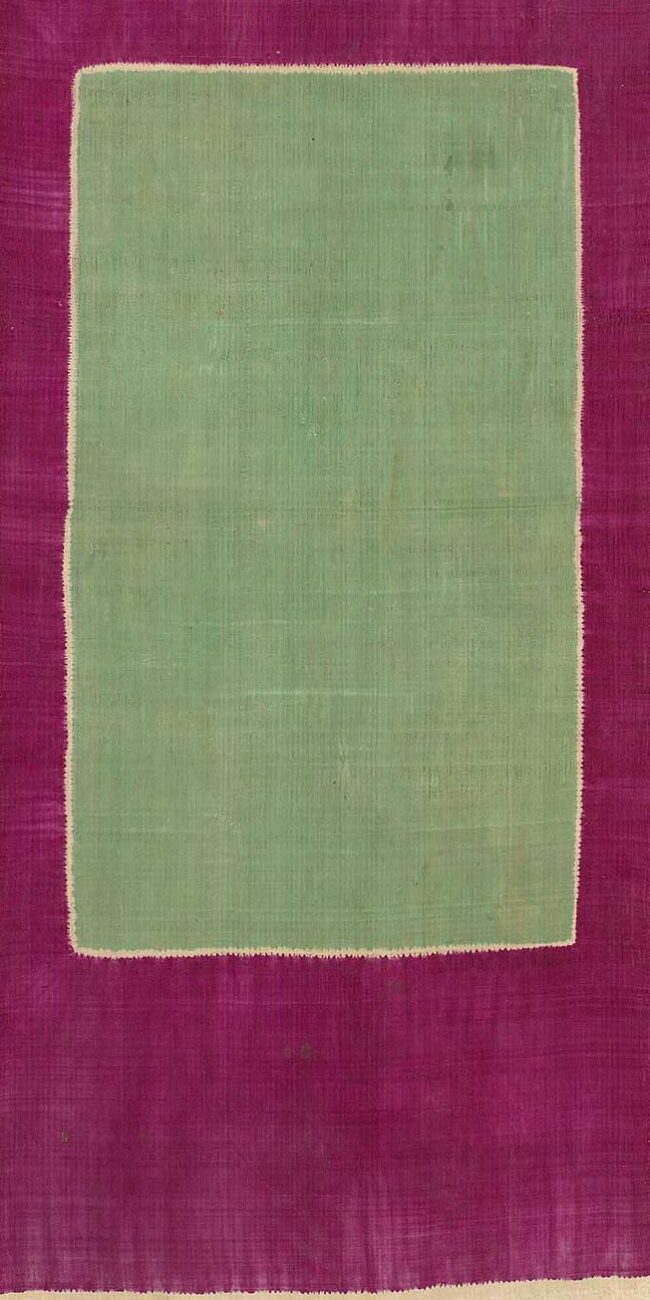

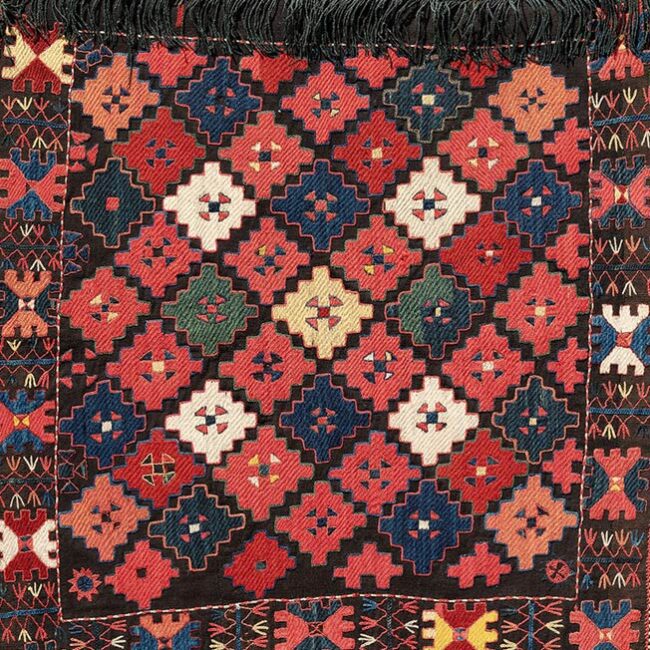

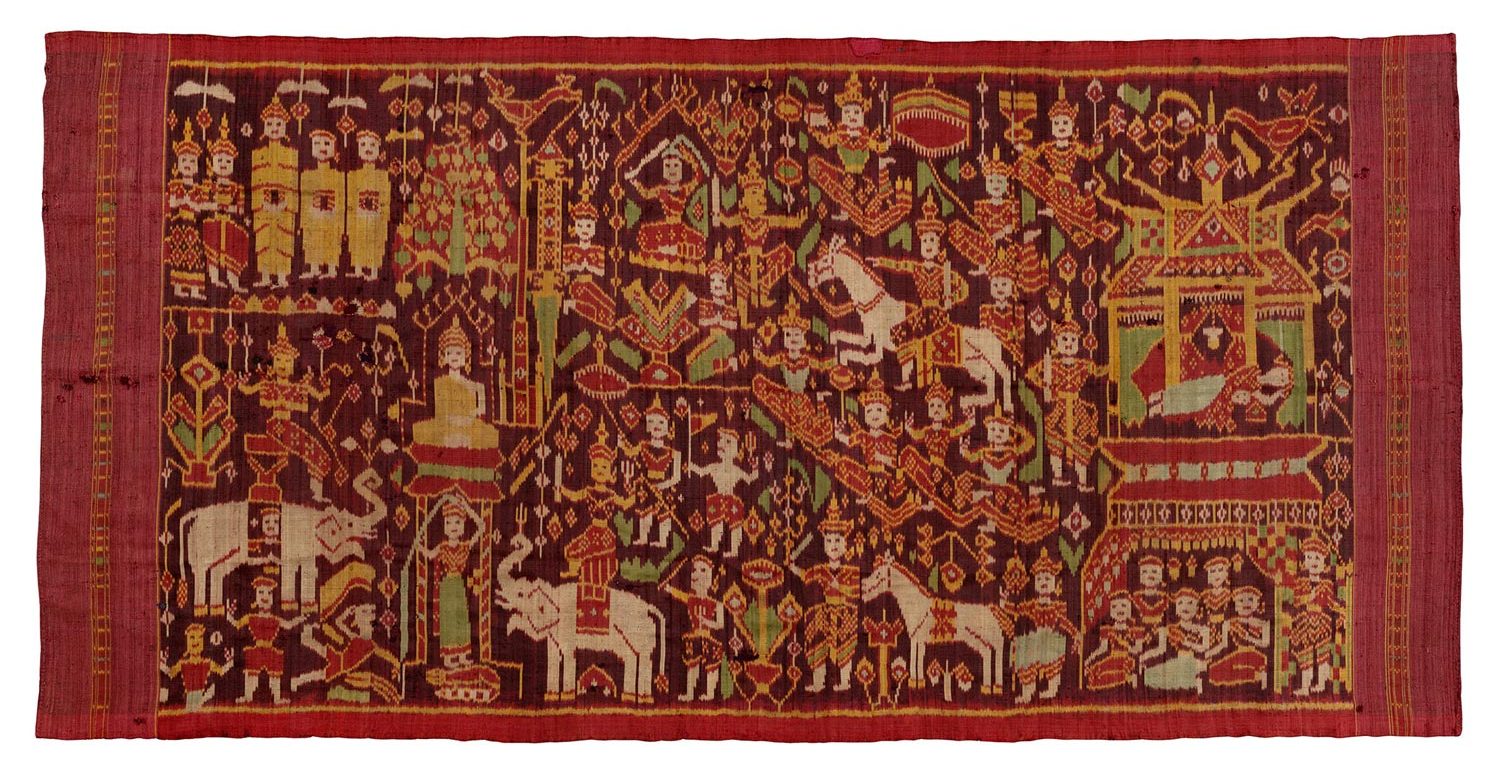

At first view, there does not seem to be an organizing theme that brings this special exhibition of textiles from India, Borneo, Sumba, Sumatra, Taiwan and Hokkaido together. The unifying principles are: classism of type; spiritual potency; a strong aesthetic, be it figural, geometric abstraction or minimalism; and superb weaving and dyeing. I would also like to draw attention to the new publication, Textiles of Indonesia, featuring brilliant photography and essays by thirteen contributing scholars.

Asia Week New York 2022

March 16-25, 2022

Important Indian, Indonesian and Other Textiles

Featured are important works of visual art, independent of culture, time or place. They are, in a word, “Enchanting.”

At first view, there does not seem to be an organizing theme that brings this special exhibition of textiles from India, Borneo, Sumba, Sumatra, Taiwan and Hokkaido together. The unifying principles are: classism of type; spiritual potency; a strong aesthetic, be it figural, geometric abstraction or minimalism; and superb weaving and dyeing. I would also like to draw attention to the new publication, Textiles of Indonesia, featuring brilliant photography and essays by thirteen contributing scholars.