Sumba Expedition

Island of Sumba, 2016

The island of Sumba may be found on a map between Bali and New Guinea but it exists in its own world, far apart from those antipodal lands. Divided east and west by language and environmental conditions, the west tends to be more wet and green and the east, dryer. Both sides of the island feature pristine beaches and some scenic mountainous zones, but do not forget to take your malaria medicine!

Sumbanese religion, Marapu, recognizes that a dualistic symmetry exists in the universe, that of male and female, hot and cold, sun and moon, cloth and metal. Here there are good and bad spirits hovering nearby, needing ritual offerings on a regular basis. The ancestors must most especially be cared for.

Sumba is thus home to one of the strongest animistic tribal societies found in Indonesia, perhaps most famous for its notorious custom of cutting off the heads of enemies and placing them on the branches of a designated tree, the pohon andung, at the entrance of the village. Such trees represented the Tree of Life as well as serving to remind viewers of the power of the raja.

Sumba has a rich megalithic heritage, featuring giant stone tomb memorials. Sumbanese houses, particularly the customary houses found in royal villages, known as rumah adat, are understood to be cosmic diagrams, with the underworld of the animals below, the mid-level for human habitation and the high roof being the realm of the ancestors. This is also the place where the pusaka heirloom treasures are stored, to be closer to the departed souls; precious gold jewelry and fabulously rare and beautiful textiles were kept just under the peak of the roof on both sides of the island. But the art of weaving and dyeing achieved greatest heights in the east, with ikat textiles adding bright colors to the dusty brown background of this, the dry side of the island.

The process of ikat is rather well known and I will offer only a cursory review of the principles. All aspects of weaving and dyeing are the sacred labor of women, except for the constructing of the backstrap loom, which is done by men. Cotton is planted, harvested, spun into thread, and wrapped in a very orderly manner around a pair of warp beams. The warp yarns are then tied with resists made from fibers that do not permit dye to pass, a few at a time, creating a pattern over the field. These now knotted bundles of threads are dipped in vats of natural plant dye progressively over time to achieve increasingly intense color. Indigo requires fermentation and turns blue only upon oxidation when the cotton yarns are exposed to air. The root dye, morinda citrifolia, creates a deep red but the cotton needs first to be tanned with a mordant to allow the red dye to bond with the cotton cellulose. After multiple dippings, some of the knotted resists may be opened, others covered up, exposing or protecting zones from the next dye bath. This permits a total of four colors: natural white, blue, red, and a blue-red combination that appears black. Mud dye is also known as an alternative means to create a blackish color.

After further drying, the yarns are stretched again, this time on a backstrap loom, where a weft is passed back and forth between alternating warps that go up and down, technically speaking, a shuttle passing between sheds. Slowly but surely, between a woman’s other duties of planting and harvesting, tending animals and children, a cloth of great beauty emerges. Depending on the intended purpose or the status of the intended wearer, some textiles will be enhanced with additional supplementary warp patterning. Others may have a fifth gold color stained on, yellow dye not lending itself to the ikat technique. Some have shells or trade beads added. There are men’s wraps called hinggi in east Sumba and hanggi in west Sumba. Queen’s sarongs are called lau. Head wraps are known as tiara. Counter-intuitively, some of the very finest textiles were created to be buried in. Thankfully, some of these survived above ground as heirlooms, retained by families to recall the deceased. From them we may know a quality of cloth intended for eternity.

Suffice it to say, we are talking about a very complex and challenging operation where something can go wrong at every juncture and sometimes does. That it does not happen more often is a testament to the artistry of indigenous women, the origins of which are lost in the mists of time. Scholar Christopher Buckley offers convincing evidence that the backstrap loom and the ikat dyeing process date back to the arrival of the Austronesian culture to Indonesia, some several thousands of years before our current era.

On Sumba, the death of a noble requires a big funeral, often taking years to prepare for. Textiles play a prominent role, beginning with the body being wrapped in dozens of cloths, many crafted especially for the occasion. Others are donated, brought by visitors coming to pay their respects from neighboring villages, near and far. Clan treasuries may be opened to permit the display of treasured Indian trade cloths, including double ikat silk patolas or printed and painted kain batik India.

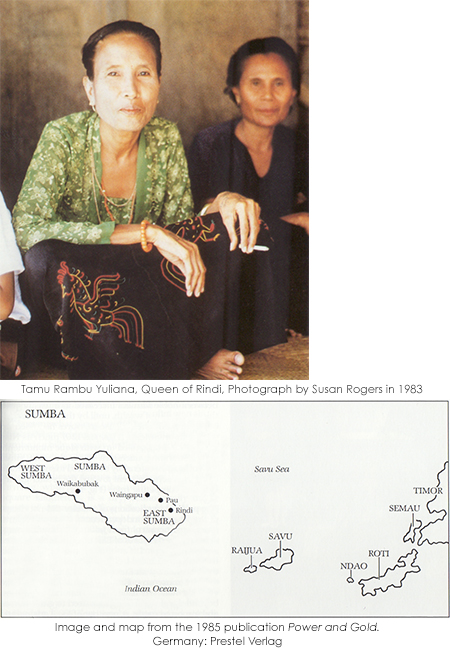

In 2003, my friend and colleague Joanne Leach and I were privileged to be invited to the funeral of Tamu Rambu Yuliana, Queen of Rindi, east Sumba. This profound, historic ritual took place in the royal village of Prai Yawang, where she lived her whole life as a guardian of the customary law, unable to marry because there was no one of sufficient high rank in the “husband giving” neighboring village to match her high status.

I first met Queen Yuliana in 1994 at a time when I was going around from royal village to royal village, on a mission to interview as many elderly queens as possible. I wanted to know if they still remembered the meaning of different motifs they incorporated into the weavings they made in their youth. Unlike the others, I found it very difficult to get Queen Yuliana to open up; it took more than one visit to make progress with her. She tested how serious I was, eventually showing me part but not all of her textile collection, and telling me the age and history of the pieces, but only as long as I gave her a carton of cigarettes and fifty US dollars! She made money without having to part with her treasures!

I came back many times and got to know other members of Yuliana’s extended family, including Umbu Kanabu Ndaung, who became king with Yuliana’s passing, and his beautiful wife, Ramu Rambu Hamu Eti, a legendary weaver and the daughter of the late, great, Raja Pau. From them I learned of Yuliana’s passing and the approximate time the funeral would take place…subject to change depending on the alignment of the stars and the reading of oracular pigs’ livers. Joanne and I were barely able to make all the necessary connecting flights from California once the final auspicious date was selected, departing San Francisco to Sydney, on to Denpasar, Bali, connecting to Waingapu, the capital of east Sumba, in less than 3 days!

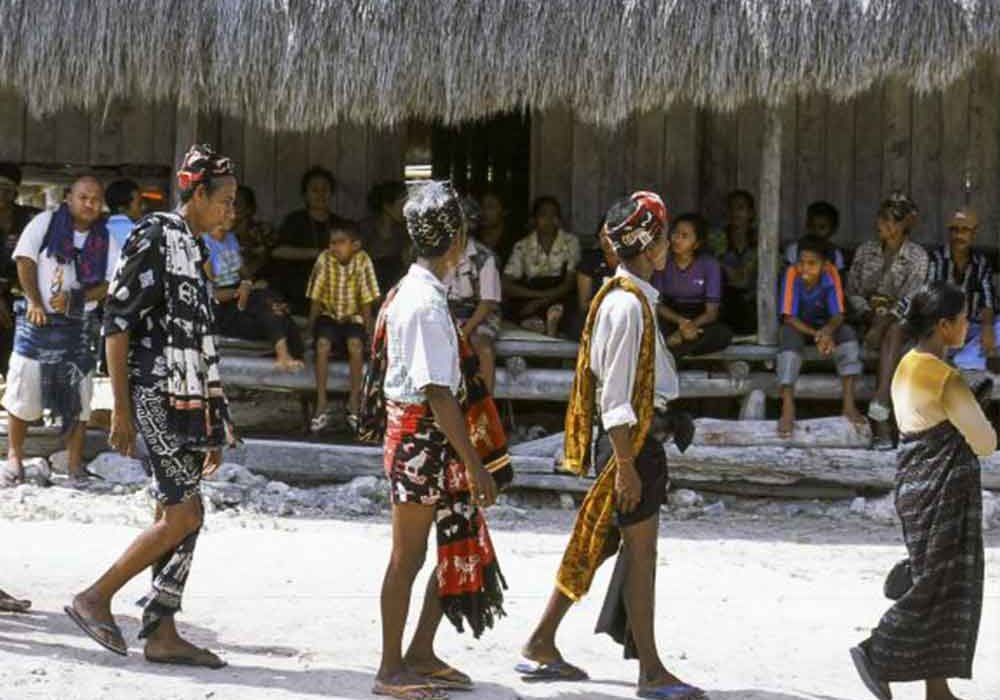

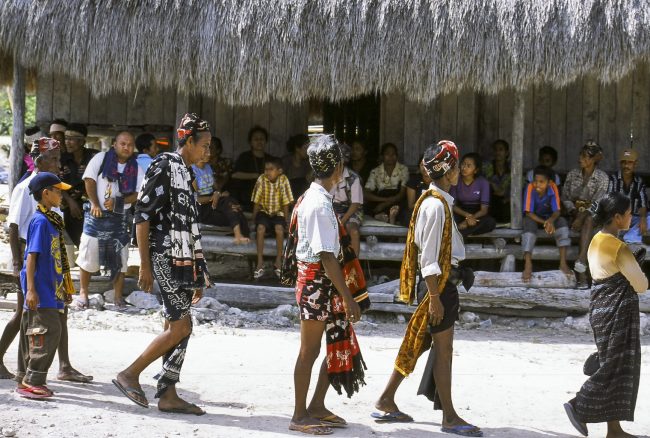

Presented here is a photo essay of what we saw. These photos were taken either by Joanne or me; we share the photo credits equally. The sequence starts with several images that give a sense of Sumba as a place, including the shoreline, rice fields, villages perched on hills, megalithic tombs and traditional high roof houses.

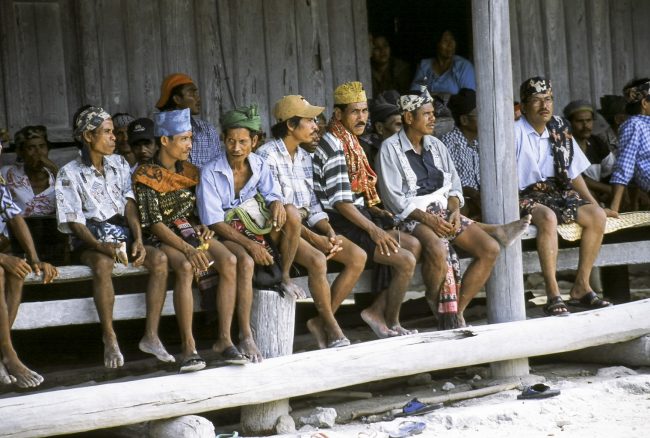

Then the funeral documentation begins, showing men and women in separate lines coming into the village of Rindi to pay their last respects. Please note the classicism of their costumes.

There seemed to be 1000 Sumbanese visitors and only ten Westerners, all the foreigners in full traditional costume; visitors included William Ingram and Jean Howe and their respected Threads of Life team, a couple of surfers, Joanne and myself and noted scholar and passionate lover of all things Sumba, Georges Breguet, who was commissioned to write an article documenting the event for the Barbier Mueller Museum. I will give a link to his article at the bottom of this essay. I wish to note here that I am forever grateful that Georges served as the communication channel from the royal household to keep me informed about the funeral schedule and its changing dates! (The last image in the photo series shows Georges Breguet and me sitting with Rindi noblemen of the Uma Andungu lineage.)

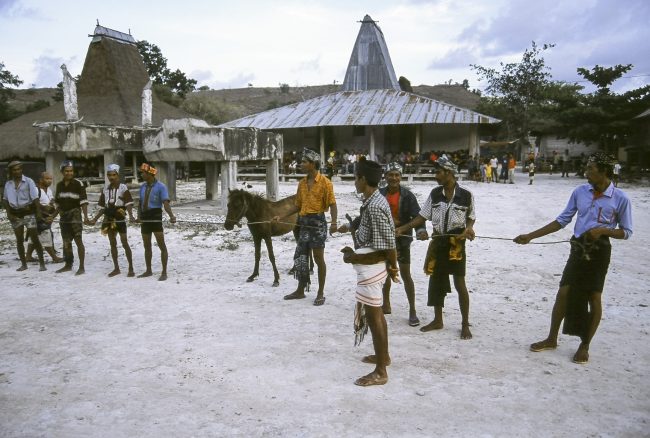

The ceremony extended for days but we came especially for the burial, which included lots of animals sacrificed to accompany the queen to the next world. These days, water buffalo, horses and pigs are dispatched, however, in former times, there would have been human sacrifices as well, to ensure the presence of servants to accompany deceased royalty into their new life.

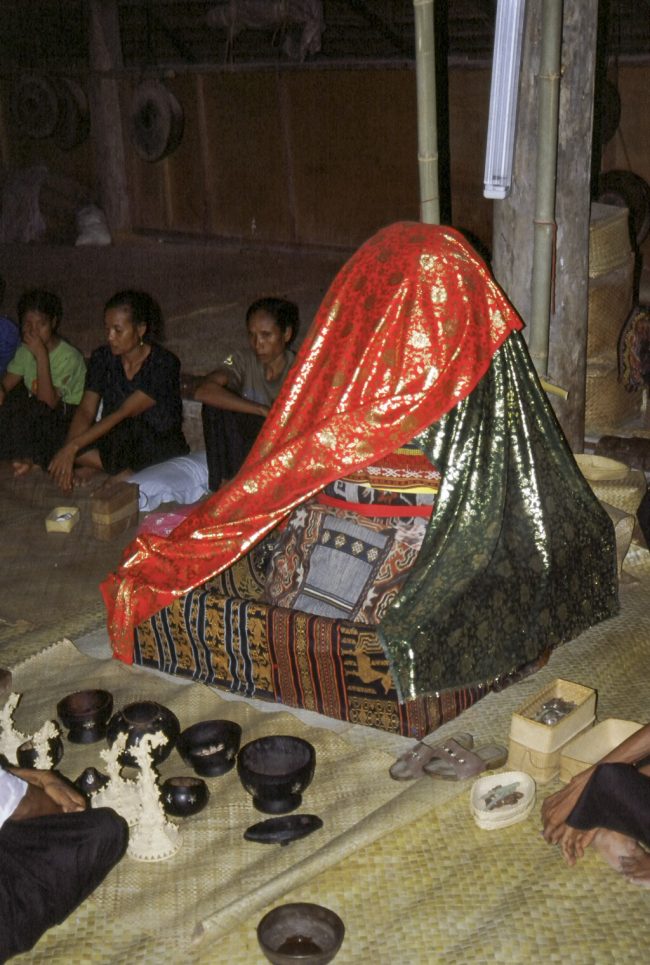

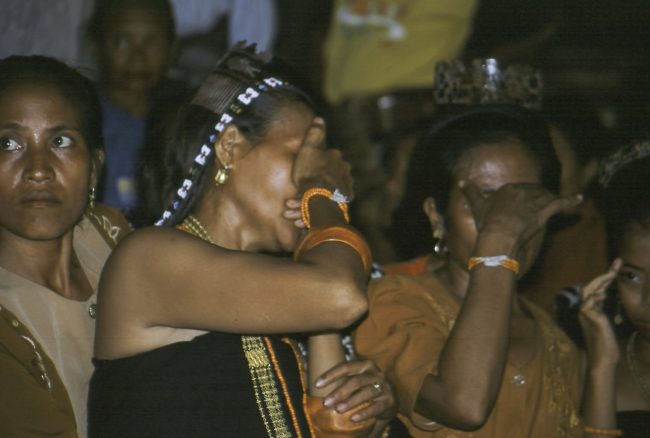

The guests gathered outside in front of the grand central meeting hall, the rumah adat. Joanne and I were invited inside, where we heard high-pitched wailing from women surrounding the queen, who was wrapped in layers and layers of textiles. As our eyes adjusted, we could see a beaded basket hanging near the deceased, which we came to understand was where food for the ancestors was offered. There were textiles hanging from the crossbeams above and bowls of sirih pinang (betel nuts, leaves and lime powder) placed as offerings before the textile-enshrouded body. Many of the villagers present were palpably in deep mourning. The next image shows Ramu Rambu Hamu Eti with one of her older relatives; she is wearing a royal necklace composed of precious orange trade beads known as muti salah that date back 2000 years.

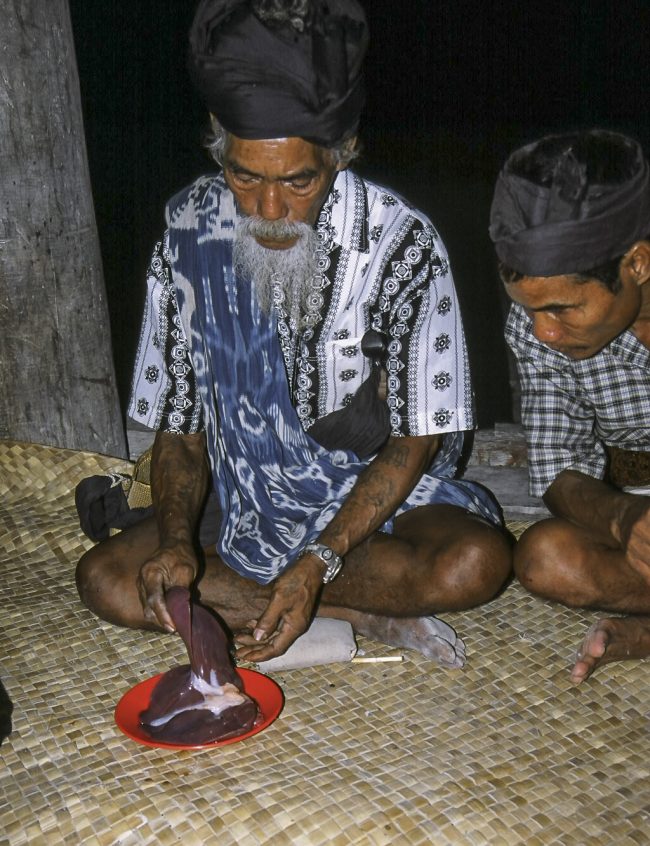

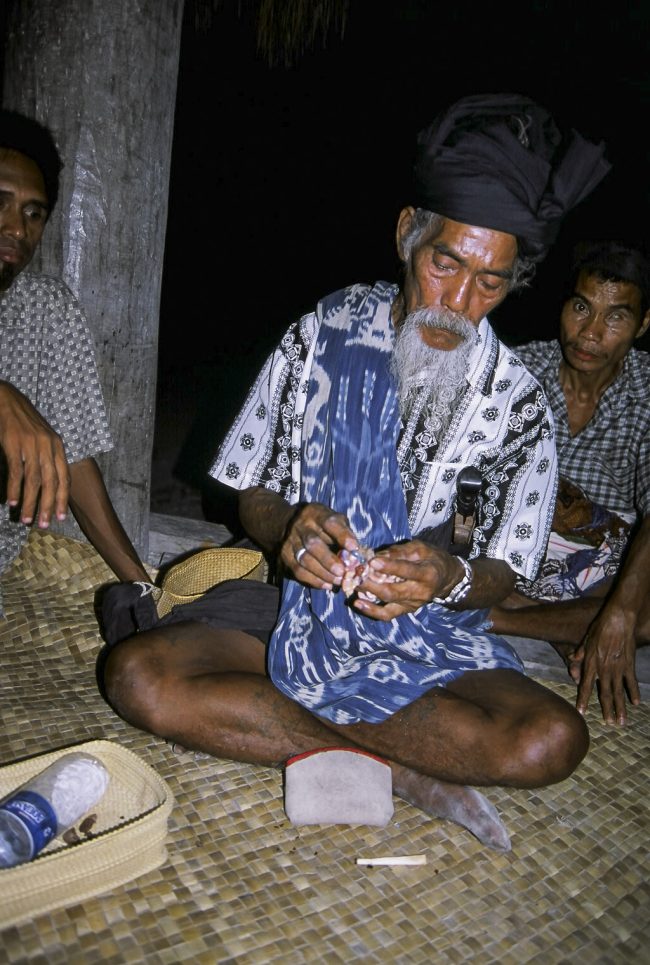

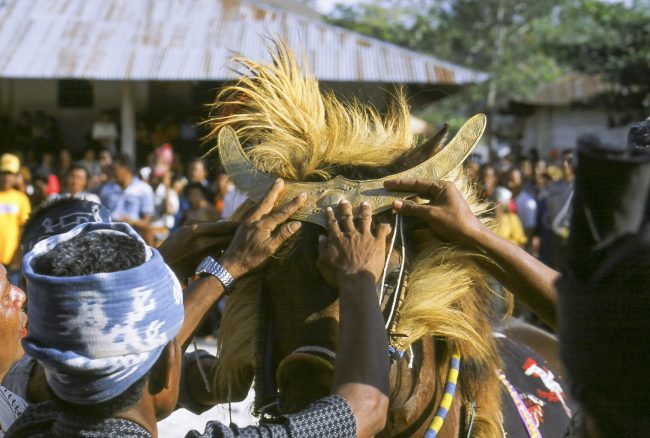

A marapu shaman read the entrails of a pig: the ceremony was allowed to go on. A male and a female servant of the queen were dressed up in royal costumes and entered into a trance state, thereby becoming a papanggangu, “one who crosses over to the land of the dead.” A horse was similarly decorated with gold jewelry to lead the procession in due course from the house to the tomb. These papanggangu would have in earlier times been the slaves dispatched to the other world, who could spend their last day of life as a king and queen. Thankfully that custom is no more, although there are whispers of what happens when the crowds and police go home…

Guests sat on the verandas of great houses. It was shockingly hot, utterly devastating, even the locals were wilting! The ritual sacrifice of animals began; this slaughter was very hard to watch, even for someone like me who has become somewhat inured to seeing the death of water buffalo as part of the funerary rites of the Toraja people of Sulawesi, with whom I have spent much time. There were many killed, the most valuable having the greatest horn spread, with legendary horns gracing doorways of royal quarters forever after. That said, I was greatly saddened to bear witness to the death of horses, eighteen in all. The living bankrupt themselves in order to pay for these excesses but woe to the person or village who would not hock themselves to the hilt in order to bring a high value animal to send off.

Twilight came and the burial took place beneath a great stone slab. Out of discretion, we did not take photos at that holy moment, sorry to disappoint. Yet I present in this slide series a related megalithic style tomb situated nearby, but made of cement. The tomb of Tamu Rambu Yuliana, Queen of Rindi, east Sumba, by contrast, had a slab of the thickest stone quarried from afar and carried by the community in the days preceding the internment. The images following the depiction of the megalithic style tomb include portraits of some of the people of that community. However inadequately, I hope to have conveyed something of life and death on the magical island of Sumba and given honor to the memory of my old and sometimes difficult friend, Tamu Rambu Yuliana.

I bought my first Sumba blanket (as they were called at the time) in a gallery run by Australians on Kuta Beach, in Bali, during my first journey to Indonesia in 1978. It featured what I came to understand was a pohon andung “skull tree” motif and from that time forward I was hooked! My most productive “hunting for hinggi” was not in Asia but rather in Amsterdam, where I went door to door visiting antique shops and flea markets while staying at the Christian Youth Hostel for five dollars a night back in 1981. I continued the search through the following decades and, with a little help from my friends, managed to acquire a worthy collection. I supplemented these very early pieces from Dutch collections with more recent pieces I bought on the island, as I always believed in supporting and rewarding whomever made the effort to make a beautiful ikat. It is such an achievement.

For those readers who made it this far and would like to understand more about Sumba culture as viewed through the prism of this funeral, please click or paste in this link to my good friend, Georges Breguet’s fabulous article:

“The Life and Death of Tamu Rambu Yuliana, Princess of Sumba.”

The technical steps of ikat are well explained by Dutch scholar/collector Peter ten Hoopen on his website, which I highly recommend to those who may be interested to know more about this challenging textile patterning technique: http://www.ikat.us/ikat_process.php

Christopher Buckley presents us with two great contributions to the field, both of which may be found online on academia.edu: