Tana Toraja, Indonesia

Sulawesi (the Celebes), 2011

The Toraja reside in the isolated mountainous interior of Sulawesi, formerly called the Celebes, plural for the many “petals” of this orchid shaped island.

Their name means “highlander” in the language of their coastal neighbors, the Buginese, and this has been my favorite place in Indonesia since I first visited it in 1980. This land is beautiful and the people fascinating but please let the photos tell the tale. In the meantime I have prepared this little introduction to help contextualize what it is you will see.

Much has been written about the Sa’dan Toraja People since their “discovery” by Western Colonial administrators, missionaries and ethnologists in the beginning of the 20th Century and for that reason I will offer only a brief introduction. Theirs is an ancient way of life that follows Aluk to Dolo “the way to the ancestors.” Rituals dating from Neolithic times and re-enforced by myth, assured fertility, status and distribution of wealth. Their houses are noted for a saddle-shaped roof, thought to recall the boats that first brought them to this island from mainland SE Asia thousands of years ago.

Headhunting was formerly a prominent feature of traditional Toraja society, but this is seldom encountered today. However their other primary social marker, i.e. funerals of great chiefs, remains unabated.

Here we may see a sacred building housing the coffins of the deceased royalty raised on high, as well as a giant temporary village for all the guests who come from great distances. I was always welcomed as a distant cousin of the deceased, who in coming from America was showing proper respect; as such I would be given a place to sit, a cup of strong Toraja coffee with a bowl of rice and barbecue. I in turn would offer a carton of cigarettes for the relatives and bags of candies for the small children as my way of saying thank you!

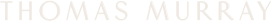

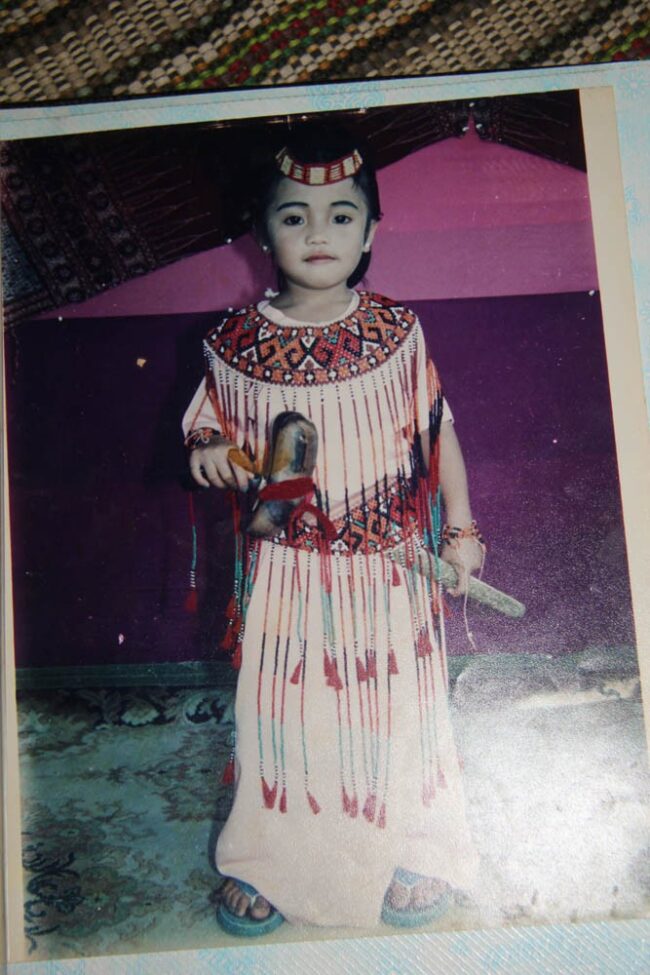

Conspicuous displays of textiles, golden dagger krises and fine beadwork abound, although a sharp eye will recognize these are nearly all recent reproductions. Owing to the tremendous financial pressure to host such funerary occasions, it may be said that most noble families were obliged to sell their authentic treasured heirlooms at least two decades ago, just to pay their share in the competition to “donate” the most buffalo to a funeral ceremony of a high-ranking relative. This may be understood to be very akin to the potlach system of wealth re-distribution by the Indians of the Pacific Northwest Coast, with its regrettable implications for a downward economic spiral. But to contextualize within their culture, by this self-imposed impoverishment, they honor the dead and avoid having an angry ghosts be visited upon them, plus a major gain of status within the community, not to mention increasing the possibility they might inherit a portion of the late king’s land and thereby renew their wealth.

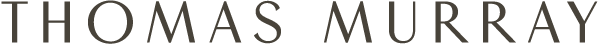

The integration into the deep Toraja rituals of recently woven cloths and beadwork, some even originally intended for the tourist market as seen in photos of a sarita banner hanging from a long bamboo pole in the accompanying slide show makes one question the whole idea of what is fake and what is real when it comes to tribal art because for centuries women have been weaving new clothes for ceremonies, or to replace damaged pieces and to have something to barter.

We speak of a dynamic culture not a static one. And in a hundred years, won’t anthropologists take great interest in cloths we see now as recent but by then will be antique and the ceremonies that we are now fortunate to see and to share will by then be the stuff of legend?

The slow rhythmic dancing in circles of different clans to pay homage to the dead would always be followed by the raising of stone megaliths and great animal sacrifices, especially the slaying of sacred water buffalos, (the most precious being white albinos worth twenty times a normal buffalo). This is the Toraja animal totem par excellence and you will see stylized images of buffalo heads on tomb and granary doors and even churches where although parishioners sing very loud in the choir it can be said there is but a thin veneer of Christianity, the “new” religion, that overlays Aluk to Dolo.

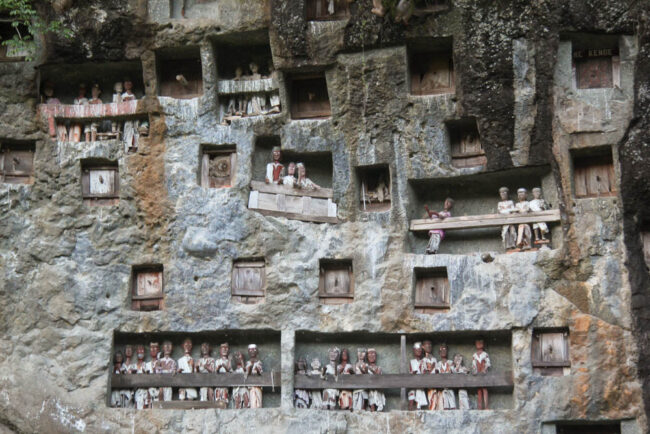

Shown in these photos is just such a funeral ceremony, followed by images of the traditional burial grounds in cliffs and caves. The presence of effigies of the dead called tau-tau, little people, may be seen in cliffs, as well as a mix of ancient and modern wood tombs.

There is also the image of the wife of my friend Camma, the Queen of Batutumonga with her young child, lest we think only about death and funerals. Just before her picture, are shots I took of photos from an old family album showing amongst other images, the last great king, and her relative, sitting in state, while the family prepares for his funeral that could be years away.

Please note as well the great tongkonan ancestral houses, many covered with the horns and jaw bones of past buffalo and pig sacrifices; in their architecture, these structures represent an ancient Austronesian diagram of the cosmos: the world of animals below, the world of humans on the mid level and the realm of the ancestors in the highest reaches of the building which is where heirlooms are kept. In one slide you will see there is a photo of me with my friend Laso, the king of Kete Kesu. I need not point out the size difference!

It was fun to introduce my traveling companion Imron who had never been to Tana Toraja, the Land of the Toraja, and in this way view for myself all of the wonders fresh and anew. So too, I would like to share some of the images I took along the way with you, respected reader!

I close the slide show with a contrast between two of the buildings we encountered on our way to the Makassar airport six hours away from Toraja Land, down the winding mountains and along the scenic coast lined with Muslim fisherman villages. The first shows a house composed of interlaced leaves, plaiting being the earliest form of architecture as practiced by the ancient Austronesian migrants (possibly 2-3000 BC), not only to make walls for their buildings but also to make the sails of their boats. We contrast this with the compelling if not somewhat intimidating architecture of a newly built mosque, reflecting the relatively recent import of Islam to which the Bugis and Makassarese took refuge in the beginning of the 17th Century.